Hey Thom

Heard you'd gone. Heard it through the e-mail grapevine, which I can't imagine ever became your style - you, an artisan of the old school, skilled of hand and sharp of eye, happy to strap on an electric guitar but happier still when picking blues from the jumbo acoustic I recall as your trademark. Born under the earthy Bull, you belonged to tradition as much as any Thomas Hardy hero.

That much you made clear when we first met, you and our little gang: us the arch-modernists, impatient for a new world which we already had buttoned down and buttoned up, though we were scarcely out of spots; you the wise but mocking voice of experience, scornful of our ignorance, though your handful of years extra seems slight enough now. Where you go, we follow.

Our common ground, too, was the old; the Black Lion our den, a bolt down a dark alley off St. Giles' holy row, a pagan pit where you performed, a Saxon bard, a mustachio'd warrior with a guitar. You used to joke about having 'This Machine Kills' stencilled on your axe, Woody style.

The music was tradition as well; blues dredged from the ancient river-banks and swamps of the Nene delta, from the bail-toters of Far Cotton, from the infirmary of Jimmy's End. From you we learnt that dusting our broom wasn't a housewive's chore, that a hellhound on our trail wasn't the threatening bark of the estate nutter's alsatian. Could white men play the blues? You had the answer, there in a 12-bar tune whose lyrics are still with me:'I wanna be a blues guitarist,

just like Mr. Peter Green.

I wanna be like Eric Clapton,

formerly with The Cream.

I don't want to be no pop star,

and have all the fortune and fame.

I just want everybody to know,

that the Blues is my middle name.'

Folk was your real middle name, of course, something we knew nothing of, except that it went with beards and duffle coats and you couldn't dance to it, certainly not pull to it, though the wild-haired girls who posed with Dylan albums in the Lion, and on whom you were on oh-so personal terms, suggested, intriguingly, that one might.

You knew all about folk, having travelled the secret beatnik paths of Albion, from Stratford-on-Avon to Oxford, from Charing Cross Road to Cheltenham, from Kingston-on-Thames to St. Ives. No-one ever did play a better version of 'Angie'. You could pick, pluck, strum, put a finger in your ear and keen like a Yorkshire shepherd. You knew about Richard and Mimi Farina, Dave Von Ronk and Greenwich Village, and had the only auto-harp I ever got near, and you thought Dylan was bit of a tosser.

You, a farter and guffawer, were no respecter of reputations. Onstage in the Lion, with boy wonder Mark at your side, you became your own legend, as the Flying Garrick soared. You were our personal star, the only local hero our stuffy small town seemed likely to have. Later, our pal Alan proved otherwise, but even he, name on a million tongues, would genuflect to you. You never did seem to hanker after the greater glory your talents could have bagged.

Offstage you moocked us with nick-names - the Stick Insect, the Mad Hatter, the Poison Dwarf - and we loved you the more for it, for lifting us out of our mundane shoe-town selves. Thanks to you, we became part of a bigger drama. For the smart alecs from the Grammar, you had special torture. You: the engraver, a creator like Blake, skilled in acid and art. Us: theorists, wankers, class traitors even, though your nose for the phoney smelt the era's hot-to-Trot pseudo-revolutionaries a country mile away, and you didn't intend to bestuck at any worker's bench. You told us tales that openedour appetites - women, places, music, the usual stuff.

Your cussed streak made Cool your sometime enemy. Heaven knows what you made of us Mod dandies, with our Italian shoes and green mohair suits, our full-length blue suedes, Italian scooters and flashy cars, our little dances that looked so neat. You never were one for doing Mickey's Monkey or skanking to Phoenix City - not your style.

You liked our drugs though, our bennies and blues. We took them to dance till dawn, you gobbled them to play on and on, till fingertips frayed. The Grovel Hovel - another of your names, for Mick's bare cellar flat off the Kettering Road - was a musical education in itself. There we'd find ourselves - there was nowhere else to go - Mick blowing harp at your feet, the rest of us saucer-eyed and coming down. Sad, sweet and deranged the songs that floated across the Racecourse from that tiny basement. Here's one you claimed you had learned 'while walking down Wardour Street one Sunday morning, from a little moddy boy lying in the gutter.' You always did exaggerate.'Oh goodbye dubes, for evermore

My restless days will soon be o'er

I've had a good time, I couldn't agree

But you see what dubes have done for me.

One black, one green, one inbetween

One red, one blue, and a yellow one too.

I've had a good time, I could not agree

But you see what dubes have done for me.'

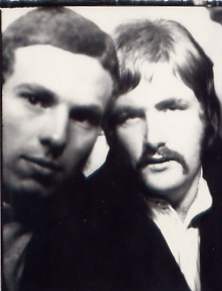

True to Taurus, you were a dresser yourself. It was an iron-grey pinstripe jacket when we hung out. Still got a photo of you in my sister's front room - a Christmas lunchtime is my recollection, wags hanging out in the uncomprehending 'burbs - with you perfectly clipped and in control, a drunken good-looking pal in tow. Found another snap, a photo-booth special from some mad Saturday maybe; Mick with button-eyes and razor parting; you bleary in a Steptoe shirt, devil of a good-looker even on a come-down.

You liked our women too, our pale, skinny girls with too much mascara. We went crazy to impress them, married them or lost them (sometimes both). You charmed them, and found a beautiful wife, but by then my time with you was on the wane.

Hippy briefly made a kind of sense of us all, drew together dirty blues and rotten rock and folkish stuff into a new deal. Your Dubious Blues Band was an era's cameo; the poster had you grinning beneath a Zapata 'tache, your head a bird cage full of wonders, though yours were no dippy Stringband visions.

It was around then we lost touch, you and those of us who fled to cities which didn't understand pewter tankards and bramble-filled hedgerows. You stayed, endured, the best spirit of a town I'd come to hate.

The last time I saw you, early Eighties I think (Christ, can it have been so far back?), you were on the corner of a sun-baked shopping parade in back street Abington, a perfect pose in knee-breeches, long white socks, buckles at your feet, hair and 'tache intact, broad smile beneath that rail-straight nose, Diane glowing by your side, the pair of you the very spirit of Albion. I, successfully metropolitan, successfully single, felt restless under your gaze. We talked junk shops and Fairports and auto-harps (not so oddly, you'd just bought another). As I bid farewell and turned away, you two seemed not to move, your married completion indulging an incomplete friend. So we left it.

God bless you Thom, and thanks.

Credit: Neil Spencer, London Fri, Aug 1st 2003 (22 years ago)